We usually think of inequality in terms of income or wealth. But the point of income and wealth is their exchange value: what you can get with them. Besides status and influence, that would be stuff you can buy, now or later: housing, food, healthcare, transportation, entertainment, education, clothing, security, experiences, etc. One would think that inequality in buying power would translate to a similar level of inequality in the value of the stuff bought. One would be wrong.

This is a tale told in three charts. The charts don’t tell the whole story.

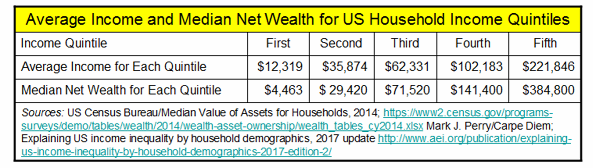

First, income and wealth inequality:

Note that household levels of income and wealth don’t actually overlap as neatly as the above chart suggests. Some low-income households are pretty wealthy (think retirees) and some low-wealth households are high-income (think young professionals). And the chart doesn’t address extreme income and wealth, just the average and median for each quintile of income. For more on the relationship between income and wealth, I recommend Inequalities in household wealth across OECD countries: Evidence from the OECD Wealth Distribution Database by Carlotta Balestra and Richard Tonkin.

Now, spending per income level:

A couple things really stand out here. One is that affluent households have more people - almost twice as many as the very poor. That’s because low-income households are more likely to consist of single individuals, especially young adults and the elderly. The other thing is that at the lower income levels, self-reported spending is greater than self-reported income. Possible explanations: unreported income, unpaid debt, gifts or non-cash government transfers reported as expenditures, and incorrect estimates of expenditures. However, housing is the main expenditure for lower income households (about 40% of total expenditures) and it’s pretty easy to estimate housing costs (especially for renters), so I’m guessing that some combination of the first three explanations are more likely.

Putting it all together:

Ok, this is all very approximate, but the pattern’s still clear. Wealth inequality is much greater than income inequality and income inequality is twice as large as consumption inequality. Mostly this is because the wealthy save and invest most of their money and low-income households often have access to resources that aren’t reported as income. None of this is to be complacent about inequality, only to have a better sense of how inequality impacts everyday life.

Reference:

Inequalities in household wealth across OECD countries: Evidence from the OECD Wealth Distribution Database Carlotta Balestra and Richard Tonkin/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Working Paper No.88 June 2018