California’s pretrial diversion programs allow eligible criminal defendants to avoid jail time by undergoing treatment. Upon successful completion of diversion, the case is dismissed and the arrest record gets sealed as though it never happened. San Francisco provides a variety of pretrial diversion programs to defendants with complex needs, including those with mental illness, substance abuse issues, felony charges, and long criminal histories. San Francisco’s diversion programs last up to two years and can be very intensive. People in these programs are assigned to a case manager and a treatment plan, which could include counseling, employment, training, graffiti cleanup and other requirements. Participation is supervised and most people complete their programs without picking up a new charge or being accused of violating their probation or parole.

But are these diversion programs successful in keeping participants out of trouble after they complete their programs? Per a recent San Francisco Chronicle article, the answer would appear to be yes:

“Lacoe’s study, which examined the impact of diversion referral in San Francisco on people charged with felony crimes from 2009 to 2017, found that people sent through diversion programs were less likely to be re-arrested and convicted than people sent through the traditional court process.” - Data shows a large increase in diversion under S.F. District Attorney Chesa Boudin. Here’s how it works. By Susie Neilson and Joshua Sharpe/San Francisco Chronicle May 11, 2022

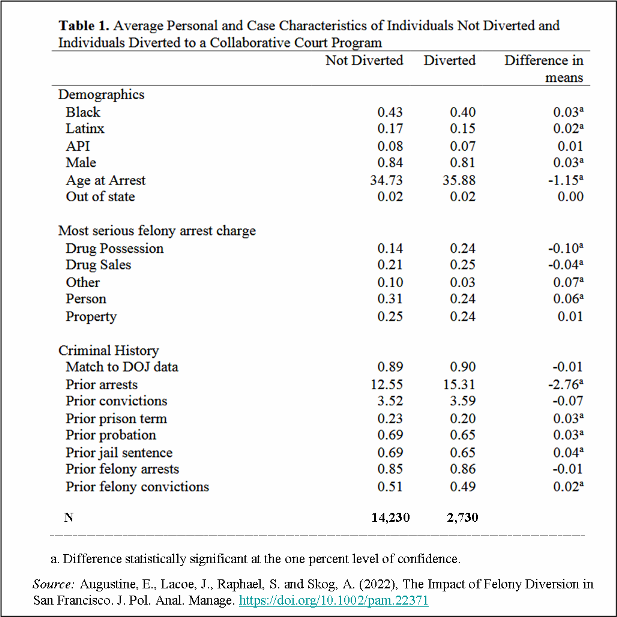

My first reaction to reading this was to wonder if defendants sent to diversion were different in some important way than those who either were not offered diversion or declined the offer (e.g., preferring to just do their time or get their charges dismissed in some other way). As it turns out, the authors of the study did compare characteristics of the diverted and non-diverted, as follows:

At first glance, the diverted and non-diverted look pretty well matched, except that drug offenses are the most serious felony arrest charge for almost half the individuals in diversion programs, compared to 35% for the non-diverted. Unfortunately, the information on the criminal history of the two groups is pretty useless, given that the categories used are too broad to be meaningful, e.g., prior felony arrests or convictions could include a single arrest and conviction for drug possession or multiple arrests/convictions for robbery. In other words, the study doesn’t provide enough information to address the impact of group differences on outcomes.

And then there’s the issue of outcome time frame. Per the Chronicle article, “people sent through diversion programs were less likely to be re-arrested and convicted than people sent through the traditional court process.” Over what period of time? Once again, the study authors seemed to have addressed this question:

Ok, for two years. But per the footnote in the above table, not two years from completion of diversion but two years from case arraignment, which happens before referral to a diversion program. And remember that diversion programs may last up to two years and participation is often closely monitored. Bottom line: the sample for these diversion “outcomes” includes individuals who are still in their diversion programs. Normally, treatment outcome studies address what happens to participants after - not during - treatment.

Also, note that none of the diversion outcome data for new arrests are statistically significant. And the conviction data isn’t all that impressive either: only Latinx participants showing a statistically significant dip in new convictions by Year 2.

So is it true that San Francisco’s diversion program participants were “less likely to be re-arrested and convicted than people sent through the traditional court process”, as claimed in the Chronicle article. No. Why the positive spin? Why make the research results look better than they are? I’m guessing it’s mostly a matter of political agenda, both of the journalists and the researchers. But that’s another story.

For the record, I’m a big fan of diversion programs. But these programs need to be based on high-quality evidence that reveals what works best for whom, and what doesn’t work. Diversion clearly doesn’t work for everyone. And by “work” I mean prevent future criminal activity - especially after completion of the program. When it doesn’t work, we need to identify the problem and try to fix it. For example, why do some groups appear to benefit more from diversion than others? I could suggest possible answers (program-individual mismatch, insufficient monitoring, lack of family support), but those are just guesses. For real answers, we need less agenda-driven research that basically seeks to sell diversion programs to the public and policymakers, and more results-oriented research that seeks to solve thorny problems.