The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) is an international assessment that measures the skills and knowledge of 15-year-old students in mathematics, reading and science. Eighty-one countries and economies took part in the 2022 PISA assessment.

My last post compared the PISA scores of immigrants and non-immigrants in various developed countries. In several of these countries, non-immigrants outperformed immigrants. Part of this performance gap can be explained by socio-economic and language factors, e.g., poverty and lack of fluency in the language used on the tests. I imagine age at immigration matters as well: a person who immigrates as a teenager will likely find school harder in their new country than someone who arrived as a baby. Following this logic, I’d expect second-generation immigrants - born in a country to at least one foreign-born parent - would have little difficulty adapting to a country’s education system and so their PISA scores would be higher than the scores of immigrants in general. Which is what I found for PISA reading scores in the developed countries I looked at:

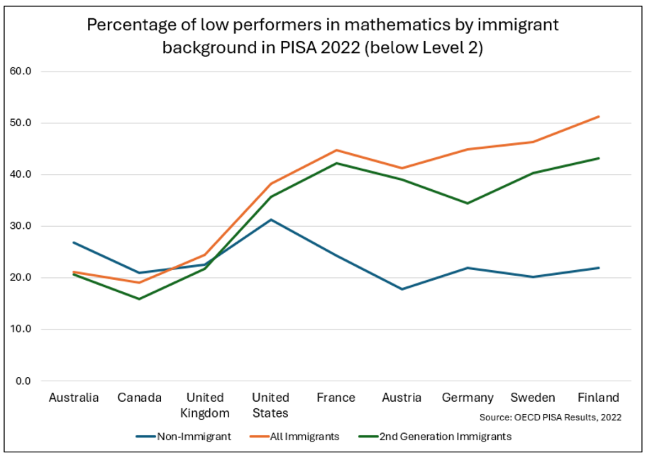

Note: Level 2 is considered the minimum level of proficiency that all students should acquire by the end of secondary education.

Per the above chart, in English-speaking countries, the low-performance rate of second-generation immigrants is similar to that of non-immigrants. Then again, the rate of low performers among all immigrants isn’t that different from that of non-immigrants in these countries, possibly because many first generation immigrants already read and speak English, a definite advantage in school.

But for the rest of the countries, the rate of low-performers in reading is abysmally high among immigrants, including the second-generation.

What about low performance rates in mathematics?

Note: Level 2 is considered the minimum level of proficiency that all students should acquire by the end of secondary education.

Pretty much the same pattern in mathematics as with reading, except that low-performance rates are higher for all immigrants, with the exception of Australia, Canada and the UK (perhaps due to the greater prevalence of high-skilled Asian immigrants in these countries).

Three questions:

Why aren’t second-generation immigrants doing better in reading in France, Austria, Germany, Sweden and Finland?

Why aren’t second-generation immigrants doing better in math in the US, France, Austria, Germany, Sweden and Finland?

Why does any of this matter?

Questions 1 and 2 are beyond the scope of this series. I’ll wrestle with question 3 in the next post.